The Problem with Visual Novels

by Andrew Erickson

Let’s talk about visual novels. By and large they’re poorly written and full of porn, and I could leave it at that, but I want to take a look at why the format has jumped headlong into appealing to the lowest common denominator. In theory, it should make for all kinds of interesting stories: they’re like novels, but with sound and graphics and maybe reader interaction! There are so many possibilities, what could possibly go wrong?

The first issue is one of market expectations. A lot of early VNs had sex, so it became something customers expected. Tsukihime wasn’t going to have sex scenes, but someone at Type Moon figured it wouldn’t move as many units without them, and so the world was subjected to Nasu’s idea of erotica. In a self-reinforcing loop, it doesn’t matter what type of story a VN is, sex has to be in it somewhere because that’s the way things work, like how nobody in America votes for third parties because nobody votes for third parties. And the end result is an inferior product. With sex as an expected feature, it’s easy to see why the market skews so heavily toward dating sims. Even western imitations of Japanese VNs, like Katawa Shoujo, follow this lead, even though it is absolutely unnecessary. Of all the directions they could have taken a story about a disabled kid adjusting to his new life, they decided to go the safe route of making everything about predictable story paths centered around whichever girl is most sexually appealing to the reader. Collect all 5, get a bonus image in the gallery. Unlike Type Moon, there was no commercial pressure forcing them to take things in that direction, they just did it because it’s the path of least resistance. Analogue – which is a commercial product – leaves out the sex itself but still centers its story around trying to “sell” a female character to the reader, as if it’s impossible for men to relate to women who aren’t intensely interested in their dick (and undercutting Analogue’s attempted feminist narrative in the process). The key choice in the story is which of two girls the reader wants to save, but it’s also feasible to save both and get a harem ending. In a sci-fi detective story about a lost colony ship, the absolute last thing I’m interested in is earning arbitrary relationship points with a virtual girl. But doing new things is challenging from a creative standpoint and risks alienating an audience that knows what it wants.

Actually, Katawa Shoujo is a very illuminating example of this. Take the infamous anal encounter on one of the routes: according to a member of the writing staff, nobody wanted to write it, but they collectively decided that there had to at least one anal sex scene. So they drew straws, the person on Emi’s route lost, and that was that. It doesn’t add anything, but it had to be in there because the writers expected that readers would expect it. Even the title shows the cargo cult-like devotion to imitating other VNs; Katawa Shoujo was written in English by a multinational staff, but the title just had to be in Japanese. And it has to be set in a Japanese high school (though everyone’s 18, honest, trust us), and the student council has to factor into it, and the protagonist is a transfer student, and on and on in an attempt to be as safe as possible. Everything from story premises to the sex scenes is determined not by what would make for an interesting scenario, but by what the safe option is. It’s an approach that, disappointingly, too many developers follow.

Secondly, the actual quality of writing in VNs tends to be midling to poor. A VN can have music and graphics, sure, but they’re only gimmicks if the writing itself, the core of the experience, is lacking. A well-written book will stimulate the reader’s mind so that they envision a scenario and play it out in their head as they read. VN writers can count on that work being done for them, so evocative descriptions don’t seem as important as in plain text. I feel that the nature of the format encourages bad writing habits; if you want the reader to feel sad, just put some slow piano music in there and maybe apply a sepia filter or something, no need to put effort into writing a touching scene. No need to describe the characters’ feelings when their portraits are right there on the screen, with a stock selection of emotions to display. And the end result of all this is something closer to a script than a novel, so bare-boned it can’t stand on its own. But then, quality writing isn’t that high a priority when the main selling point of a story is foxgirl tits. Expecting anything but the most basic, half-assed writing is putting the cart before the horse, I think. It’s like the problem light novels predominantly face: they exist in a twilight zone between proper books and manga, and end up with the good points of neither.

And third, VNs need to let go of their emphasis on event flags and routes. Wanting to get readers involved in a story is understandable, but “choose your own adventure” stories are a niche gimmick for a reason. Instead of telling a single, tightly focused story, VN writers have to divide their attention between every possible scenario that can play out in a playthrough. Scenes have to be rewritten to account for decisions made four hours previously, which I’m sure adds something to the experience in the abstract, but it can’t be worth the tradeoff of a weaker overarching story. By that I mean that having a plethora of routes adds some degree of replay value, in reality people are simply going to look up a walkthrough to get where they want. On the other hand, I often pick up and reread books I’ve already read several times, because a finely crafted narrative is going to be enjoyable more than once; I notice new things and appreciate parts of the story in a new light. A good story has consistent themes and strong characters. But how do you not weaken those if you turn control of a narrative over to the reader? That’s a problem most VN writers don’t seem to consider, which ties into why so many of the choices boil down to deciding which girl to sleep with; it’s the least challenging kind of story interaction to write, because the other prospective love interests can be safely jettisoned from the story, conveniently eliminating any questions of character development. They take a shotgun-like approach of having a half dozen weaker narrative threads instead of a single strong one, but storytelling is an area where quality trumps quantity every time. Otherwise, the Twilight series would be the quintessential vampire story instead of Dracula.

Not to say the problems endemic to VNs are insurmountable. There are good VNs, but they tend to be the ones that break with convention. BlazBlue’s story is presented, essentially, as a VN, but combines that with gameplay so that it doesn’t have to lean on standard VN tropes for appeal. ArcSys simply uses the VN format the way other games use cutscenes, which works so effectively that I’m amazed more VNs don’t make the jump to having some form of gameplay beyond clicking on one of several preselected options at set points in the story. The difference between the BlazBlue approach and more conventional VNs is like that between, say, Command & Conquer and an FMV game. For those who didn’t live through that unfortunate era of gaming, the larger storage space of CDs compared to cartridges sparked a fad in the 90s of releasing games consisting almost completely of cutscenes. It was an attempt to make gaming cinematic by removing the game part of the game, like Heavy Rain and Gone Home; and gamers were smart enough to realize that releasing a lazy, stripped-down game isn’t exciting or cinematic so much as it’s bad design. After all, just because something is possible, that doesn’t at all mean that it should be done. It would be nice if VN readers had a similar epiphany so that companies would stop churning out the most derivative titles they can get away with. I’m not saying that every VN has to try to be a proper game, but I would appreciate something to do other than advance dialogue and select one of several interchangeable love interests. Someone could at least go to the trouble of creating a setting and story that makes sense for the format they’re working with.

Even discounting BlazBlue as a fighting game first and VN second, Ace Attorney and Dangan Ronpa both take advantage of their status as VNs and use it to further the story. Both are, at their core, mystery stories, so giving choices to the player makes sense, as does the limited selection of choices (there can only be so many culprits, after all). The reader is engaged because the decisions depend on their intelligence and understanding of the story. Each series also has a cohesive, distinctive art direction rather than trying their hardest to ape a generic anime style. In each case, the choice to present the story as a VN brings something to the table that wouldn’t necessarily be there in straight prose. I can’t say the same is the case for most VNs, which don’t play to the strengths of the medium. They don’t have to all be murder mysteries, but it helps to choose a story structure and tone that make the reader feel like the choices are meaningful.

Though that raises the question of whether VNs have to have choices at all. Across some 16 When They Cry VNs, I can count the number of decisions presented to the player on one hand, each of which activates an alternate ending. The effect is immediate and obvious and not some pointless filler like “do I want to eat Japanese-style pizza or regular pizza?” If my immediate reaction when presented with a dilemma is “who cares,” then maybe the writers did a poor job making me care about their story and characters. It isn’t even that the writing in When They Cry is particularly good – it isn’t, and a good editor could have slashed the word count by half without losing anything important – but it’s different. Looking past Ryukishi’s bloated prose and the Touhou-quality character art (which I’ll grant is hard to do, those portraits are incredibly distracting), at least there’s an attempt to tell a story that isn’t an excuse for porn. That should be the standard, not the exception, but here we are. I can’t even seriously recommend When They Cry, though it does serve as a useful contrast. Ryukishi knew the kind of story he wanted to tell and went for it, without any apparent concern for what’s expected of a VN. I can respect that. A tightly focused story, one that knows what it is, is preferable to a VN that presents the reader with dozens of choices, in the process making none of them significant. I can’t fault When They Cry for its ambition, only its results.

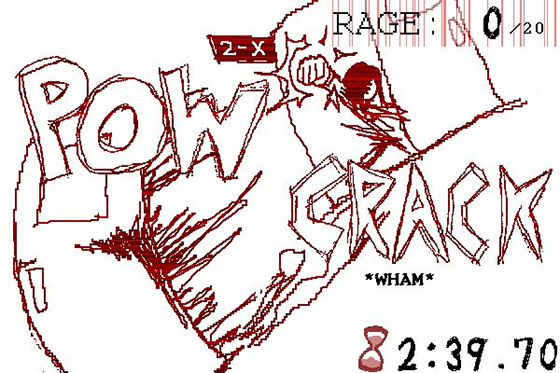

But I’m not going to be completely negative here. There is one VN I think everybody should take a look at, if only because it’ such a small time investment, there’s no harm in it. So many VNs take hours or even dozens of hours to complete, but this one has the distinction of having a time limit. In Crimsoness, the reader starts with three minutes to reach the end of the story, and anything goes. This is accomplished by filling the protagonist’s Rage Meter, which is increased by performing various actions, until she accumulates enough fury to punch the earth in half, because she’s having that bad of a day. The choices all boil down to “where to go” and “who to punch,” which I can appreciate. It’s funny, doesn’t overstay its welcome, short enough that exploring every interaction is easy, and even the slapdash MS Paint art somehow feels appropriate. Sure, it’s shallow, but it’s a story about someone botching an exam and going on a school rampage that involves wrangling an alligator, so I didn’t ask for nor expect any deep themes. It is what it is. And sometimes that’s all you can ask for.

Peace. And remember: just say no to waifus.

Follow Us!